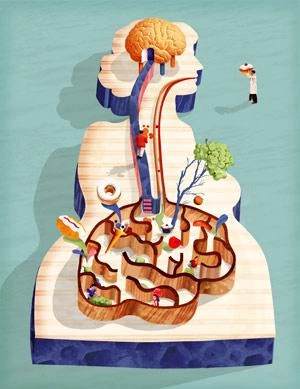

Did You Know You Have a Second Brain? Learn What It Is and Why It Matters

When I studied anatomy in college many years ago my professor never mentioned the enteric nervous system. This term refers to the network of neurons lining our guts and is responsible for that feeling of “butterflies” in your stomach. In fact, there is exactly one paragraph in my Anatomy and Physiology book that deals with that subject. It says: “The enteric nervous system has roughly as many neurons as the spinal cord, and as many neurotransmitters as the brain. The specific functions and interactions of these neurotransmitters in the enteric nervous system remain largely unknown.”

It seems like the interest in the enteric nervous system has been going through a renaissance lately. Some scientists even call it “a second brain” now for its ability to call the shots in certain matters.

“In evolutionary terms, it makes sense that the body has two brains,” said Dr. David Wingate, a professor of gastrointestinal science at the University of London and a consultant at Royal London Hospital. “The first nervous systems were in tubular animals that stuck to rocks and waited for food to pass by. As life evolved, animals needed a more complex brain for finding food and sex and so developed a central nervous system. But the gut’s nervous system was too important to put inside the newborn head with long connections going down to the body. Offspring need to eat and digest food at birth. Therefore, nature seems to have preserved the enteric nervous system as an independent circuit inside higher animals. It is only loosely connected to the central nervous system [via the vagus nerve] and can mostly function alone, without instructions from topside.”(1)

“The second brain doesn’t help with the great thought processes…religion, philosophy and poetry is left to the brain in the head,” says Michael Gershon, chairman of the Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology at New York–Presbyterian Hospital/Columbia University Medical Center who wrote the book The Second Brain. But this multitude of neurons in the enteric nervous system enables us to “feel” the inner world of our gut and its contents. Much of this power is directed at the complex process of digestion. (3) On top of that, the gut is at the front lines of the immune response since it has to detect dangerous bacteria or viruses that might sneak in with our food. The immune cells in the gut then secrete inflammatory substances, including histamine, which signals to the second brain to trigger diarrhea, or pass on the message to the first brain to trigger vomiting. (2)

However, “The system is way too complicated to have evolved only to make sure things move out of your colon,” says Emeran Mayer, professor of physiology, psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles (U.C.L.A.). (3) “A big part of our emotions are probably influenced by the nerves in our gut,” Mayer says. That feeling of “butterflies” in the stomach is just one example of the gut’s response to excitement, fear or stress. “A lot of the information that the gut sends to the brain affects well-being, and doesn’t even come to consciousness,” says Michael Gershon.

After all, 95% of body’s serotonin is found in the bowels. Serotonin is best known as a “feel-good” neurotransmitter involved in preventing depression and regulating sleep, appetite and body temperature; it transmits signals from the gut to the brain. Research shows that stimulation of the vagus nerve (that sends signals from the gut to the brain) can be an effective treatment for chronic depression that has failed to respond to other treatments (The British Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 189, p 282).

There is also a growing body of research that demonstrates that the second brain is implicated in a wide variety of brain disorders. In Parkinson’s disease, for example, the problems with movement and muscle control are caused by a loss of dopamine-producing cells in the brain. However, Heiko Braak at the University of Frankfurt, Germany, has found that the protein clumps that do the damage, called Lewy bodies, also show up in dopamine-producing neurons in the gut. In fact, judging by the distribution of Lewy bodies in people who died of Parkinson’s, Braak thinks it actually starts in the gut, as the result of an environmental trigger such as a virus, and then spreads to the brain via the vagus nerve.” Likewise, the characteristic plaques or tangles found in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s are present in neurons in their guts too. (2)

Pankaj Pasricha, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Neurogastroenterology in Baltimore, Maryland, points out that without the gut there would be no energy to sustain life. “Its vitality and healthy functioning is so critical that the brain needs to have a direct and intimate connection with the gut,” he says. (2) That connection is maintained via the vagus nerve.

I am sure you have heard of the vagus nerve. All of the sudden everybody is interested in stimulating it, either via electrodes planted in the body or other, more holistic methods (like yoga and acupuncture). Research into yoga and its effects on the vagus nerve may show yet another facet of yoga practice’s benefits.

Another YogaUOnline article, this time by Kristine Kaoverii Weber, reviewing the vagus nerve’s contribution to psychological health.

Reprinted with permission from SequenceWiz.

Educated as a school teacher, Olga Kabel has been teaching yoga for over 14 years. She completed multiple Yoga Teacher Training Programs, but discovered the strongest connection to the Krishnamacharya/ T.K.V. Desikachar lineage. She had studied with Gary Kraftsow and American Viniyoga Institute (2004-2006) and received her Viniyoga Teacher diploma in July 2006 becoming an AVI-certified Yoga Therapist in April 2011. Olga is a founder and managing director of Sequence Wiz– a web-based yoga sequence builder that assists yoga teachers and yoga therapists in creating and organizing yoga practices. It also features simple, informational articles on how to sequence yoga practices for maximum effectiveness. Olga strongly believes in the healing power of this ancient discipline on every level: physical, psychological, and spiritual. She strives to make yoga practices accessible to students of any age, physical ability and medical history specializing in helping her students relieve muscle aches and pains, manage stress and anxiety, and develop mental focus.

Educated as a school teacher, Olga Kabel has been teaching yoga for over 14 years. She completed multiple Yoga Teacher Training Programs, but discovered the strongest connection to the Krishnamacharya/ T.K.V. Desikachar lineage. She had studied with Gary Kraftsow and American Viniyoga Institute (2004-2006) and received her Viniyoga Teacher diploma in July 2006 becoming an AVI-certified Yoga Therapist in April 2011. Olga is a founder and managing director of Sequence Wiz– a web-based yoga sequence builder that assists yoga teachers and yoga therapists in creating and organizing yoga practices. It also features simple, informational articles on how to sequence yoga practices for maximum effectiveness. Olga strongly believes in the healing power of this ancient discipline on every level: physical, psychological, and spiritual. She strives to make yoga practices accessible to students of any age, physical ability and medical history specializing in helping her students relieve muscle aches and pains, manage stress and anxiety, and develop mental focus.

Resources

Image in article from neurosciencestuff.tumblr.com

1. The Enteric Nervous System: The Brain in the Gut by King’s Psychology Network

2. Gut Instincts: The secrets of your second brain by Emma Young

3. Think Twice: How the Gut’s “Second Brain” Influences Mood and Well Being by Adam Hadhazy (Scientific American)

4. Enteric Nervous System in the Small Intestine: Pathophysiology and Clincal Implications a study by Behtash Ghazi Nezami and Shanthi Srinivasan (PubMed Central)

5. The Gut’s Little Brain in Control of Intestinal Immunity review article by Wouter J. de Jonge (International Scholarly Research Notices)